Introduction

|

| The "Spotted Horses" mural, painted by woman artists inside France's Pech Merle cave dated 23 millennium BC is a fine example of the prehistoric graphic design. According to the analysis of Pennsylvania State University archaeologist Dean Snow many of the artists working in that cave were women. Until recently, most scientists assumed the prehistoric handprints on the rockwalls around such images belong to man.National Geographic |

As a manifestation of socio-cultural evolution, the Graphic Design has played a primordial role in the history of Homo sapiens as a social being. Many hundreds of stylized compositions of animals by the primitive artists in the Chauvet Cave, in the south of France, which were drawn even before 30,000 B.C., the image of "Spotted Horses", painted by woman artists, inside France's Pech Merle cave dated 23,000 BC, as well as similar designs in the Lascaux cave of France, that were drawn more than 14,000 B.C., the Altamira cave paintings of bison between 9000 to 17000 BC, the designs of the primitive hunters in the Bhimbetka rock shelters in India that were drawn more than 7,000 B.C., the Aboriginal Rock Art, in the Kakadu National Park of Australia, and many other rock or cave paintings in other parts of the world are apt testaments to the very long history of visual communication culture that is shared among humanity.

|

| The image of a bison in Altamira Cave, Spain. |

|

| Image of a horse in the Chauvet cave. |

|

| Drawing of a horse in the Lascaux cave. |

|

| A rock drawing in Bhimbetka India. |

|

| Aboriginal Rock Art, Ubirr Art Site, Kakadu National Park, Australia |

|

| A battle image on Tassili rocks of Ajjer (Algeria), |

A good example of this art is observable on the paintings of Altamira, which are located in the deep recesses of caves in the mountains of Northern Spain, far out of the reach of the destructive forces of wind and water. As a result these paintings have been preserved rather intact from 9,000-17,000 B.C. In addition to these murals, Altamira is the only site of cave paintings in which tools, hearths and food remains also have been found. These signs shed light on the habitat, and living conditions of these prehistoric artists . Unlike the other similar caves in Europe and elsewhere, the Altamira caves show no signs of soot deposits, which perhaps suggest that the people at Altamira had slightly more advanced lighting technology emitting less smoke and soot than the torches and fat lamps which Paleolithic people are given credit for.

It should be noted that, there is no consensus among archaeologists as to when Altamira's parietal art was first created. Early investigations suggested that the most of it was created at the same time as the Lascaux cave paintings - that is, during the early period of Magdalenian art (15,000 BC). But according to the most recent research, some drawings were made between 23,000 and 34,000 BCE, during the period of Aurignacian art, contemporaneous with the Chauvet Cave paintings and the Pech-Merle cave paintings. The general style at Altamira remains that of Franco-Cantabrian cave art, as characterised by the pronounced realism of the figures represented. Indeed, Altamira's artists are renowned for how they used the natural contours of the cave to make their animal figures seem extra-real.

Like the Lascaux cave, Altamira has three types of art: coloured paintings, black drawings and rock engravings. As mentioned above, subjects are mostly animals (bison, boar, deer, horses), although there are eight anthropomorphic figures and a large amount of geometric signs and symbols.

The paintings are unique for several reasons. First, they are composed of many different colours (up to three colours in a single animal), more than is common in most other examples of parietal art. The bisons in particular are depicted in varying shades, making them appear astonishingly lifelike. Second, the animals - twenty-five of which are depicted in life-size proportions - are depicted with unusual accuracy. The bisons are especially well rendered; so too is the red deer. Other animals are also depicted in detail, down to the texture of their fur and manes. Third, when composing their pictures, the Magdalenian artists took full advantage of the natural contours, facets and angles of the rock surface to make the figures as three-dimensional as possible.

The Altamiran artists primarily focused on bison, which was a main economic resource for them. Not only as a source of food, but also other useful commodities like skin, bones and fur. These prehistoric artists used natural earth pigments like ochre and zinc oxides, some of the images are painted with three colors. This is a significant artistic achievement, particularly when taken into consideration the masterly execution of the animal's anatomy, and their accurate physical proportions.

In Tassili-n-Ajjer in Algeria, one of the most famous of North African sites of rock painting, various images depict a historical evolution. This historical documentation of mankind evolution is something that graphic design has always done, and will do so in future. Tassili paintings depict at least four distinct chronological periods, which are: an archaic tradition depicting wild animals whose antiquity is unknown but certainly goes back well before 4500 B.C.; a so-called bovidian tradition, which corresponds to the arrival of cattle in North Africa between 4500 and 4000 B.C.; a "horse" tradition, which corresponds to the appearance of horses in the North African archaeological record from about 2000 B.C. onward; and a "camel" tradition, which emerges around the time of Christ when these animals first appear in North Africa.

|

| The paintings of the Chauvet cave depict a stunning menagerie of the beasts that roamed Ice Age Europe 35,000 years ago. |

|

| Paintings are not the only traces of the human presence: as the soil remained untouched, twenty footprints of a preteen, fireplaces and flint tools with traces of use are also present. |

Our ancient ancestors were far less isolated from nature than we are today. Unlike us who exhibit a tendency to distance ourselves from the animals by creating urban centers they cohabited with them. Before, they adopted a sedentary lifestyle, nomadic groups, like other living creatures, lived most of their lives in search of food. In 1863-64, the French geologist Édouard Lartet, and his friends Henry Christy excavated a number of caves and rockshelters at Cro-Magnon near the town of Les Eyzies-de-Tayac in the Dordogne region of southwestern France, where they found a number of ancient human skeletons. It was during their excavation of La Madeleine that the engraved drawing of a mammoth on mammoth ivory along with stone tools provided incontrovertible proof of human antiquity, as well as evidence of art before agriculture and settled life. They uncovered five archaeological layers, where the human bones found in the topmost layer proved to be between 10,000 and 35,000 years old. The prehistoric humans revealed by this find were called Cro-Magnon and have since been considered, along with Neanderthals, to be representative of prehistoric humans. Modern studies suggest that Cro-Magnons emerged even earlier, perhaps as early as 45,000 years ago.

Cro-Magnons were robustly built and powerful and are presumed to have been about 166 to 171 cm tall. The body was generally heavy and solid, apparently with strong musculature. The forehead was straight, with slight browridges, and the face short and wide. Cro-Magnons were the first humans (genus Homo) to have a prominent chin. The brain capacity was about 1,600 cubic centimeter, somewhat larger than the average for modern humans. It is thought that Cro-Magnons were probably fairly tall compared with other early human species.

Instead of avoiding Chauvet Cave, a potentially dangerous place, it appears that these early humans embraced their affinity with animals and ventured into caves where predators had sought refuge. Although they had recognized the spiritual significance of the cave, they also respected that space as the domain of the cave bears. Thus, they never used this space as a shelter, but employed it only for painting and possibly for their ritual ceremonies. Instead of trying to subjugate the cave bears or occupying their place, they used the space only in special occasion.

The subjects of these paintings demonstrate the respect the artists felt for some of their animal friends. These early artists demonstrated their respect for the animals by being meticulously faithful to their anatomical detail. In fact, their art exhibits an intimate knowledge of the animal world, as is evident by their ability to accurately represent not only the appearance of animals but also their behaviors. In Chauvet, there are paintings of multiple horses shown with their mouths open giving the impression they are whinnying, rhinos fighting with legs jutting forward and horns colliding, and a male lion courting a female who is "raising her lips [and] baring her teeth." What is amazing about these pieces are the sensory response they trigger in the viewer. The viewer is able to hear the whinnies, the clashing of the horns, and the harsh growl. More importantly, the viewer feels the emotions of the animal and can understand their story. To properly display this story through painting, the artist must have felt a strong connection to these animals. In order to properly depict these stories, he or she must have been able to empathize with the animal and to understand its emotions. By empathizing with the animals, they saw themselves as a part of this animal kingdom, not necessarily above it.

Rock art is generally divided in two categories: carving sites (petroglyphs) and paintings sites (pictographs). Petroglyphs, carved or pecked into stone, are the most common form of rock art remaining in Nevada, Scandinavia, and Canada. Early artists sometimes chose a stone covered with a dark surface called desert varnish (or patina) and carved through the surface, creating an image in the lighter colored rock beneath. While desert varnish has covered the images, the original marks are still visible. Pictographs were painted onto the surfaces with red, yellow, and sometimes green pigments made from minerals or plants and other organic material. Over thousands of years, water, wind, and even people have washed away or damaged much of the paint, leaving only faint traces of some of these paintings.

|

| Mishipeshu and other pictographs at Agawa Bay – said by Thor Conway to be “the most famous image of aboriginal art in Canada” |

|

| Priest Guiding a Sacrificial Bull- Fragment of mural painting from the palace of Zimri-Lim, Mari (modern Tell Hariri, Iraq) 2040-1870 BC. |

| ||

| Wooden ushabti box and ushabtis of Pinedjem I. |

There is no doubt that ancient Egyptians were the originator of what is today defined as 'visual communication design'. The Egyptian language of antiquity used the same word, sekh, to signify writing, drawing, and painting, and from the very beginning of her history, Egypt used written message in combination with images to convey various socio-cultural values that were at the roots of her system of beliefs. More than five thousand years ago, the graphic designers of Egypt were working on a strict greed system that established conventional codes of representation in sculpture, painting, and relief. By and large, Egyptian scribes used the same conventions in the standardization of hieroglyphic signs in their system of writing. This is why the ancient Egyptian graphic design and hieroglyphs are closely correlated. For instance, the hieroglyphic ideogram for "man," is the figure of a seated man, which also appears frequently in sculptures and paintings.

The composition of the Egyptian designs are well balanced, harmonious, and adhere to certain minimalism principles. The artists abstract from play of light and shadow, and minimalize the illusion of space and atmosphere in outdoor scenes. The images are sharpened by clear outlines, and the complexity of interrelationships among spatial forms are simplified. The artists use flat areas of color to enhance order and clarity, and compose figurative scenes in horizontal registers. The figures were portrayed emotionless since artists wanted to avoid the transient aspect of life, as they were interested in eternal features and immortality.

“Greetings to you, Osiris, Lord of Eternity

King of the Two Lands, Chief of both banks…<

Youth, King, who took the White Crown for himself…

Who makes himself young again a million times…

What he loves is that every face looks up to him…

Shining youth, who is in the primordial water, born on the first of the year…

From the outflow of his limbs both lands drink.

Of him it is arranged that the corn springs forth from the water

In which he is situated….

In the Egyptian system of beliefs Gods, such as Atum and Osiris, as well as many others, played the key roles in the management of universe and all its affairs. Not only they symbolized all natural phenomena but also abstract concepts such as truth, justice, kinship, and love.

In a dialogue between Atum and Osiris in the Book of the Dead, Atum states that he will eventually destroy the world, submerging gods, men and Egypt back into Nun, the primal waters, which were all that existed at the beginning of time. In this nonexistence, Atum and Osiris will survive in the form of serpents.

Atum’s myth merged with that of the great sun god Ra, giving rise to the deity Atum-Ra. In the beginning there was only Nun, a primordial mass of unstructured water, Atum-Ra, lived in Nun. After a period of time he rose from the splendor of the Sun. Atum-Ra was the father of the gods, creating the first divine couple, Tefnut and Shu, the first female and male gods. He created these two children out of dust and his own spittle; Tefnut, was the Goddess of Moisture, and Shu was the god of Air and together with their father they formed a trinity. Tefnut and Shu, gave birth to Geb, the earth God, who married Nut, the Goddess of sky, and with her fathered four children; Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys.

Atum’s myth merged with that of the great sun god Ra, giving rise to the deity Atum-Ra. In the beginning there was only Nun, a primordial mass of unstructured water, Atum-Ra, lived in Nun. After a period of time he rose from the splendor of the Sun. Atum-Ra was the father of the gods, creating the first divine couple, Tefnut and Shu, the first female and male gods. He created these two children out of dust and his own spittle; Tefnut, was the Goddess of Moisture, and Shu was the god of Air and together with their father they formed a trinity. Tefnut and Shu, gave birth to Geb, the earth God, who married Nut, the Goddess of sky, and with her fathered four children; Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys.

|

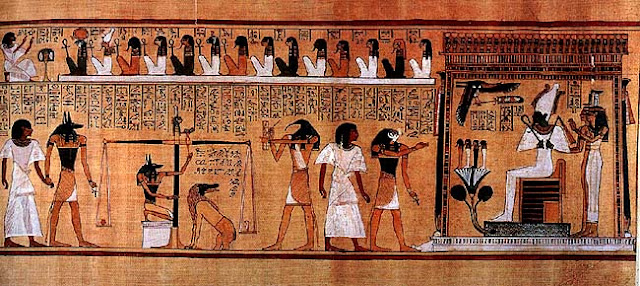

| Judgement before Osiris, from the papyrus of the scribe Hunefer, from the book of the dead of Hunefer, 19th Dynasty. 1285 BC, painted papyrus, British Museum, London |

Osiris was the ruler of the underworld. The oldest and simplest hieroglyphic form of his name is written by a "throne" and an "eye." He was the eldest offspring of Geb, the god of Earth and Nut, the goddess of sky. He married Isis, who the Book of the Dead describes as "She who gives birth to heaven and earth, knows the orphan, knows the widow, seeks justice for the poor, and shelter for the weak". Osiris and his wife Isis became the king and the queen of Egypt when his father, Geb, retired. Osiris promulgated just and fine laws for his people who were considered privileged among the mankind. Osiris then asked Isis to assume the throne of Egypt and himself traveled afar to spread his laws around the world.

When Osiris returned, Seth, his jealous brother, plotted to murder him in order to usurp his throne. Seth gave a royal banquet and offered his guests, including Osiris, a prize in the form of a magnificent coffin, which was specially built to fit Osiris’ body. The winer was supposed to be the one who best fitted in the coffin, and when Osiris tried it, Seth shut the lid and threw the coffin in the Nile river. Seth assumed the kingship, and the grieving Isis went out to look for Osiris' body, where she found it in Byblos. She brought the corpse back to Egypt, and through her powerful magic brought him back to life for a while to conceive a son, Horus, who was to avenge his father's death. Seth found the Osiris body, tore it apart into pieces, and threw them back into the Nile. Isis stubbornly searched for him and found every pieces of his body and reassembled it by papyrus bands into a mummy. Osiris then transformed to an akh, and traveled to the underworld to become king and judge of the dead.

Meanwhile Seth continued his cruel rule. Isis was hidden with her baby Horus in the marshes. When Isis went to buy food in the villages Seth's spies found where she was hiding. Seth disguised as a snake and went into her hiding place. He found Horus alone and being a snake bit and poisoned the child. The poor mother brought the baby to the villagers and asked for their help to no avail. she cried out in despair. Nephtys, her sister, advised her to stop the Sun Boat of Ra and ask him for help. Isis, who was aware of Ra's secret name, used it to stop his boat. Ra through his messenger, Thoth assured her of the safety of Horus by promising that the Sun Boat would stop untill Horus was recovered. Ra kept his promises and Horus was cured. Horus grew to become a hero, and when he was ready, Isis gave him great Magic to use against Seth. Horus found Seth and challenged him for the throne. They fought for many days, until Seth gave up, and was castrated. Horus did not kill him, lest he be just as wicked as him. A fight broke up among the Gods who supported Horus and the Gods who supported Seth. But realizing that their quarrel would disturb Ma'at, or the balance of life,they asked the wise Neith for for his arbitration. Neith ruled that Horus was the rightful heir to the throne. Thus, Horus cast Seth into Darkness, where he lives to this day, still scheming to overthrow Horus.

When Osiris returned, Seth, his jealous brother, plotted to murder him in order to usurp his throne. Seth gave a royal banquet and offered his guests, including Osiris, a prize in the form of a magnificent coffin, which was specially built to fit Osiris’ body. The winer was supposed to be the one who best fitted in the coffin, and when Osiris tried it, Seth shut the lid and threw the coffin in the Nile river. Seth assumed the kingship, and the grieving Isis went out to look for Osiris' body, where she found it in Byblos. She brought the corpse back to Egypt, and through her powerful magic brought him back to life for a while to conceive a son, Horus, who was to avenge his father's death. Seth found the Osiris body, tore it apart into pieces, and threw them back into the Nile. Isis stubbornly searched for him and found every pieces of his body and reassembled it by papyrus bands into a mummy. Osiris then transformed to an akh, and traveled to the underworld to become king and judge of the dead.

Meanwhile Seth continued his cruel rule. Isis was hidden with her baby Horus in the marshes. When Isis went to buy food in the villages Seth's spies found where she was hiding. Seth disguised as a snake and went into her hiding place. He found Horus alone and being a snake bit and poisoned the child. The poor mother brought the baby to the villagers and asked for their help to no avail. she cried out in despair. Nephtys, her sister, advised her to stop the Sun Boat of Ra and ask him for help. Isis, who was aware of Ra's secret name, used it to stop his boat. Ra through his messenger, Thoth assured her of the safety of Horus by promising that the Sun Boat would stop untill Horus was recovered. Ra kept his promises and Horus was cured. Horus grew to become a hero, and when he was ready, Isis gave him great Magic to use against Seth. Horus found Seth and challenged him for the throne. They fought for many days, until Seth gave up, and was castrated. Horus did not kill him, lest he be just as wicked as him. A fight broke up among the Gods who supported Horus and the Gods who supported Seth. But realizing that their quarrel would disturb Ma'at, or the balance of life,they asked the wise Neith for for his arbitration. Neith ruled that Horus was the rightful heir to the throne. Thus, Horus cast Seth into Darkness, where he lives to this day, still scheming to overthrow Horus.

Every king of Egypt was identified with Horus during his life and with Osiris after his death, and Egyptians performed rituals and made offerings to gain the favor of these gods who are featured prominently in their art.

Whether carving statues or painting figures, the Egyptian graphic designers used a grid system in order to adhere to a canon of aesthetics, which determined some strict ratios. As Iversen has pointed out, the Egyptians frequently referred to their works of art as being 'true', which means they wanted to represent the natural proportions, and perhaps even the true dimensions of the objects. Grids were used to control the proportions of two-dimensional relief sculpture and to line up the sides, back, and front of sculpture. The evidence of grids is often found in unfinished relief sculpture or in paintings where a layer of paint has peeled off to reveal the traces of grids. These traces have provided the data to study how Egyptian artists worked.

Grids are first appeared in 2125–1991 BC during the Eleventh Dynasty and remained in force until the end of the 26th Dynasty in the New Kingdom. The Egyptian artists first drew horizontal and vertical grid-lines on the surface of the wall they intended to paint, or on a rock they intended to carve. The grid canonically determined the aesthetic proportions of the figures, which was 18 units to the hairline, or 19 units to the top of the head. The height of the figure was usually measured to the hairline rather than the top of the head, perhaps because the head often were concealed by a crown or head piece. Various parts of body was placed on precise segments of grid lines. For instance, the connection of the neck and shoulders was placed at the row sixteenth, the elbow at the row ninth with width of six squares. The width of female figures was only between four and five squares. The face is two squares high, the shoulders are aligned at sixteen squares from the base of the figure, the elbows align at twelve from the base, and the knees at six. The grid system thus allowed artists to create striking compositions of harmony and consistency that are scalable to colossal statues or tiny figures in hieroglyphic scripts.

|

| Nebamun hunting in the marshes, fragment of a scene from the tomb-chapel of a wealthy Egyptian official called Nebamun, C. 1350 BC. |

The grammatical rules of Egyptian visual communication were framed within the two aspects of 'Frontality' and 'Axiality'. The rules of axiality meant figures were placed on an axis. Proportions of figures were related to the width of the palm of the hand so there were rules about proportions of head to body. The faces were devoid of emotional expression. Hieratic scaling dictated that the sizes of figures were determined by their importance. The proportions of children did not change; they are just depicted smaller in scale. Servants and animals were usually shown in smaller scale. In order to clearly define the social hierarchy of a situation, figures were drawn to sizes based not on their distance from the painter's point of view but on relative importance. For instance, the Pharaoh would be drawn as the largest figure in a painting no matter where he was situated, and a greater God would be drawn larger than a lesser god.

Axiality, proportion and hieratic scaling indicate that Egyptian artists would have had to use mathematics to construct their composition. Ancient Egyptian artists used vertical and horizontal reference lines in order to maintain the correct proportions in their work. The tombs walls still carry the traces of these grids used to ensure the conventions were kept to by the lower and apprentice artists working for the master artist. Political and religious, as well as artistic order was maintained in Egyptian art. Important figures were not usually depicted overlapping, but figures of servants were. Each object or element in a scene was designed and drawn from its most recognizable angle. The objects in a scene were then grouped together to create the whole. This is why images of people show their face, waist, and limbs in profile, but the eye and shoulders are shown facing frontally. These scenes are composite images designed to provide complete information about the relationship of the objects to each other, rather than from a single viewpoint.

In short, Egyptian art's perspective was complex and geared towards enhancing the harmony of a composition, while providing the most complete information. In their figurative paintings artists realizing the fact that they are representing a three dimensional geometric body in a restricted two dimensional surface, opted to add other visual dimensions to achieve their orderly aesthetics ideals while conveying a "true" message. They typically used size as one of their dimensions in order to indicates the hierarchical importance of characters. For instance, as we argued before kings are often depicted much larger than his subjects. In general, this resulted in a vertical perspective. Other dimensions were employed through multiple points of view, that would allow the human figures to be represented from the angle of view where they are best defined. Thus, heads are defined in profile with protruding nose and lips. The eyes in profile are depicted from the front view, looking at the viewers. The shoulders are seen from the front, their torsos and hips are depicted in three-quarter view point which allow the legs and arms to be seen in profile with legs extended when the figure is walking.

Distance of a figure, with respect to the viewer, is either presented by the overlapping of the bodies or by placing of the more distant figures above the ones in the foreground. However, the prominent dignitaries rarely overlap one another. Husbands and wives are depicted in a close distance from each other so that only their arms may overlap. The important peoples' bodies had to be represented complete and according to the canons. However, the lower ranking individuals, servants and slaves were often depicted as overlapping. The artists used such occasions to introduce some rhythmic repetitive patterns with these overlapping bodies so as to enhance the aesthetics of their works.

In representing objects and landscapes the artists used the same multiple points of view technique. For instance, in the image Queen Nefertari bringing an offering to Goddesses Hathor and Selkis, we can see the goddesses are sitting in profile. The table-leg in front of them is represented from front viewpoint, the tabletop is viewed directly from above. The offerings on the tabletop are arranged vertically, so that each item can be identified by the viewer.

Egyptians paid particular attention to represent various modes of production at various stages of the of work, in farming, wine making and so on. In many of their tombs, such as tomb of nakht, various scenes of daily works such as ploughing, digging, sowing, stages of the harvest: the measuring and winnowing of the grain , the reaping and pressing of the grain into baskets and so on are depicted.

Distance of a figure, with respect to the viewer, is either presented by the overlapping of the bodies or by placing of the more distant figures above the ones in the foreground. However, the prominent dignitaries rarely overlap one another. Husbands and wives are depicted in a close distance from each other so that only their arms may overlap. The important peoples' bodies had to be represented complete and according to the canons. However, the lower ranking individuals, servants and slaves were often depicted as overlapping. The artists used such occasions to introduce some rhythmic repetitive patterns with these overlapping bodies so as to enhance the aesthetics of their works.

|

| Queen Nefertari bringing an offering to Goddesses Hathor and Selkis, Tomb of Queen Nefertari, wife of Rameses IInd. Thebes. |

In representing objects and landscapes the artists used the same multiple points of view technique. For instance, in the image Queen Nefertari bringing an offering to Goddesses Hathor and Selkis, we can see the goddesses are sitting in profile. The table-leg in front of them is represented from front viewpoint, the tabletop is viewed directly from above. The offerings on the tabletop are arranged vertically, so that each item can be identified by the viewer.

Egyptians paid particular attention to represent various modes of production at various stages of the of work, in farming, wine making and so on. In many of their tombs, such as tomb of nakht, various scenes of daily works such as ploughing, digging, sowing, stages of the harvest: the measuring and winnowing of the grain , the reaping and pressing of the grain into baskets and so on are depicted.

|

| Sennedjem and his wife harvesting grain, from the tomb Sennedjems at Deir el Medina. |

|

| Production of wine - two laborers pick the grapes, the juices are then squeezed out of them by men on the left - while a man is filling jars from a tap |

The Egyptians believed that the pleasures of life including the times of prosperity could be made permanent by depicting scenes like; A feast for Nebamum, Nebamun hunting in the marshes, Sennedjem and his wife harvesting grain, Nakht and his wife sit before offerings, and so on. In these paintings the humanity rejoice, the family and friendship is glad, the nature and water resound; and the fields are jubilant. Overall, scenes of life, hunting and farming in the Nile marshes and the abundant wildlife supported by that environment symbolized rejuvenation and eternal life. As images like; Nakht hunting birds in the marsh, or Nebamun hunting in the marshes reveals, The geese, of several different species are depicted, and the colours are natural and subtle. Egyptian artists studied carefully the wildlife of their surroundings and paid utmost attention to detail in depicting the birds, fish, cattle, crocodiles, wildcats, butterflies and so on.

The Egyptian nobles were fond of elaborate parties and feasts as their main form of entertainment. Listening to music, watching dances, being served with foods, and friendly chats in an orderly and civilized manner were the main features of these parties. Both men and women were invited, and dining couches and small tables were provided for the guests, who regaled themselves with dishes of fowl, game, fish, bread, and wine. Women wore elegant dresses, and they paid particular attention to style and design of their dress, jewelery and furniture.

|

| Nebamun’s cattle, fragment of a scene from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, around 1350 BC |

|

| A feast for Nebamum, bottom half of a scene from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, C. 1350 BC |

|

| A feast for Nebamum, top half of a scene from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, C. 1350 BC |

|

| A feast for Nebamum, top half of a scene from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, C. 1350 BC |

|

| Senejem and His Wife, Tomb of Nakht |

|

| Nakht and his wife sit before offerings, Tomb of Nakht - Scribe of the Granaries (reign of Tuthmosis IV) |

|

| The tomb of Nakht; his wife tenderly holds a bird in her hand. |

|

| The tomb of Nakht, a nude young girl leaning to offer perfume to three female dignitaries. |

|

| Birds are being caught in nets and plucked. The filled net is a complex of wings and colors |

Go to the next chapter: Chapter 2 - The Medium is the Message

No comments:

Post a Comment